The surrealists' Paris, too, is a little 'universe'. ... In the

larger one, the cosmos, things look no different. There, too, are

crossroads where ghostly signals flash from the traffic, and

inconceivable analogies and connections between events are the order

of the day. It is the region from which the lyric poetry of

Surrealism reports.

- Walter Benjamin, 'Surrealism', from One Way Street (1979, p. 231)

The New Architecture seems to be making little progress in the USA ;

. . The advocates of the new style are full of earnestness, and some

of them carry on in the shrill pedagogical manner of believers in

the Single Tax . . . but, save on the level of factory design, they

do not seem to be making many converts.

-H.L.Mencken, 1931

Why brilliant fashion-designers, a notoriously non-analytic breed,

sometimes succeed in anticipating the shape of things to come better

than professional predictors, is one of the most obscure questions

in history; and, for the historian of culture, one of the most

central. It is certainly crucial to anyone who wants to understand

the impact of the age of cataclysms on the world of high culture,

the elite arts, and, above all, the avantgarde. For it is generally

accepted that these arts anticipated the actual breakdown of

liberal-bourgeois society by several years. By 1914 virtually

everything that can take shelter under the broad and rather

undefined canopy of 'modernism' was already in place: cubism;

expressionism; futurism; pure abstraction in painting; functionalism

and flight from ornament in architecture; the abandonment of

tonality in music; the break with tradition in literature.

A large number of names who would

be on most people's list of eminent 'modernists' were all mature and

productive or even famous in 1914.(Matisse and Picasso; Schonberg

and Stravinsky; Gropius and Mies van der Rohe; Proust, James Joyce,

Thomas Mann and Franz Kafka; Yeats, Ezra Pound, Alexander Blok and

Anna Akhmatova.) Even T.S. Eliot, whose poetry was not published

until 1917 and after, was by then clearly a part of the London

avant-garde scene [as a contributor (with Pound) to Wyndham Lewis's

Blast]. These children of, at the latest, the 1880s, remained icons

of modernity forty years later. That a number of men and women who

only began to emerge after the war would also make most high-culture

shortlists of eminent 'modernists' is less surprising than the

domination of the older generation.! (Among others, Isaac Babel

(1894); Le Corbusier (1897); Ernest Hemingway (1899); Bertolt

Brecht, Garcia Lorca and Hanns Eisler (all born 1898); Kurt Weill

(1900); Jean Paul Sartre (1905); and W.H. Auden (1907).Thus even

Schonberg's successors - Alban Berg and Anton Webern - belong to the

generation of the 1880s.)

In fact, the only formal

innovations after 1914 in the world of the 'established' avant-garde

seem to have been two: Dadaism, which shaded over into or

anticipated surrealism in the western half of Europe, and the

Soviet-born constructivism in the East. Constructivism, an excursion

into skeletal three-dimensional and preferably moving constructions

which have their nearest real-life analogue in some fairground

structures (giant 1 wheels, big dippers etc.), was soon absorbed

into the main stream of architecture and industrial design, largely

through the Bauhaus (of which more below). Its most ambitious

projects, such as Tatlin's famous rotating leaning tower in honour

of the Communist International, never got built, or else lived

evanescent lives as the decor of early Soviet public ritual. Novel

as it was, constructivism did little more than extend the repertoire

of architectural modernism.

Dadaism took shape among a mixed

group of exiles in Zurich (where another group of exiles under Lenin

awaited the revolution) in 1916, as an anguished but ironic nihilist

protest against world war and the society that had incubated it:

including its art. Since it rejected all art, it had no formal

characteristics, although it borrowed a few tricks from the pre-1914

cubist and futurist avant-gardes, including notably collage, or

sticking together bits and pieces, including parts of pictures.

Basically anything that might cause apoplexy among conventional

bourgeois art-lovers was acceptable Dada. Scandal was its principle

of cohesion. Thus Marcel Duchamp's (1887-1968) exhibition of a

public urinal as 'ready-made art' in New York in 1917 was entirely

in the spirit of Dada, which he joined on his return from the USA;

but his subsequent quiet refusal to have anything further to do with

art - he preferred to play chess - was not. For there was nothing

quiet about Dada.

Surrealism, while equally devoted

to the rejection of art as hitherto known, equally given to public

scandal and (as we shall see) even more attracted to social

revolution, was more than a negative protest; as might be expected

from a movement essentially centred in France, a country where every

fashion requires a theory. Indeed, we can say that, as Dada

foundered in the early 1920s with the era of war and revolution that

had given it birth, surrealism emerged from it as what has been

called 'a plea for the revival of the imagination, based on the

Unconscious as revealed by psychoanalysis, together with a new

emphasis on magic, accident, irrationality, symbols and dreams

(Willett, 1978).'

In some ways it was a romantic

revival in twentieth-century costume, but with more sense of

absurdity and fun. Unlike the mainstream 'modernist' avant-gardes,

but like Dada, surrealism had no interest in formal innovation as

such: whether the Unconscious expressed itself in a random stream of

words ('automatic writing') or in the meticulous nineteenth-century

academician's style in which Salvador Dali (1904—89) painted his

deliquescent watches in desert landscapes, was of no interest. What

counted was to recognize the capacity of the spontaneous

imagination, unmediated by rational control systems, to produce

cohesion out of the incoherent, an apparently necessary logic out of

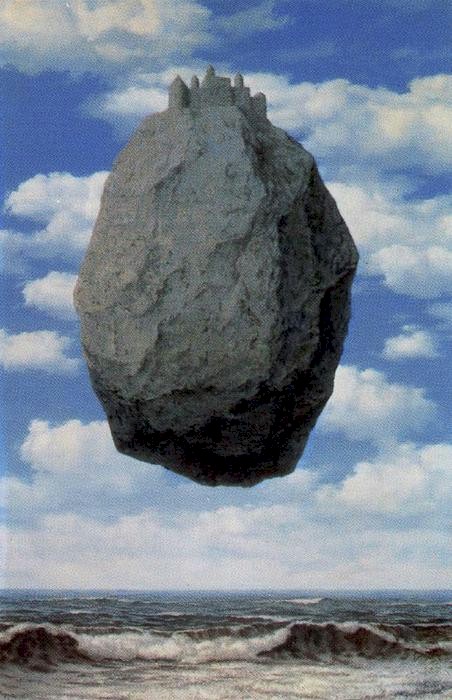

the plainly illogical or even impossible. Rene Magritte's

(1898-1967) Castle in the Pyrenees, carefully painted in the manner

of a picture-postcard, emerges from the top of a huge rock, as

though it had grown there. Only the rock, like a giant egg, is

floating through the sky above the sea, painted with equal realistic

care.

Surrealism was a genuine addition

to the repertoire of avant-garde arts, its novelty attested by the

ability to produce shock, incomprehension, or what amounted to the

same thing, a sometimes embarrassed laughter, even among the older

avant-garde. This was my own, admittedly juvenile, reaction to the

1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London, and later to a

surrealist painter friend in Paris, whose insistence on producing

the exact equivalent in oils of a photograph of human entrails I

found hard to understand. Nevertheless, in retrospect it must be

seen as a remarkably fertile movement, though chiefly in France and

countries such as the Hispanic ones, where French influence was

strong. It influenced first-rate poets in France (Eluard, Aragon);

in Spain (Garcia decors by the likes of the cubists Georges

Braque (1882-1963) and Juan Gris (1887-1927); music by, or rewritten

by Stravinsky, de Falla, Milhaud and Poulenc became de rigeur,

while both styles of dancing and choreography were modernized

accordingly. Before 1914, at least in Britain, the

'Post-Impressionist Exhibition' had been jeered by a philistine

public, while Stravinsky caused scandal wherever he went, as did the

Armory Show in New York and elsewhere. After the war, the

philistines fell silent before the provocative displays of

'modernism', deliberate declarations of independence from the

discredited pre-war world, manifestos of cultural revolution. And,

through the modernist ballet, exploiting its unique combination of

snob appeal, the magnetism of vogue (plus the new Vogue) and elite

artistic status, the avant-garde broke out of its stockade. Thanks

to Diaghilev, wrote a characteristic figure in the British cultural

journalism of the 1920s, 'the crowd has positively enjoyed

decorations by the best and most ridiculed living painters. He has

given us Modern Music without tears and Modern Painting without

laughter' (Mortimer, 1925).

Diaghilev's ballet was merely one

medium for the diffusion of the avant-garde arts which, in any case,

varied from one country to the next. Nor, indeed, was the same

avant-garde diffused throughout the Western world for, in spite of

the continued hegemony of Paris over large regions of elite culture,

reinforced after 1918 by the influx of American expatriates (the

generation of Hemingway and Scott Fitzgerald), there was actually no

longer a unified high culture in the old world. In Europe Paris

competed with the Moscow-Berlin axis, until the triumphs of Stalin

and Hitler silenced or dispersed the Russia or German avant-gardes.

The fragments of the former Habsburg and Ottoman Empires went their

own way in literature, isolated by languages which nobody seriously

or systematically attempted to translate until the era of the

anti-fascist diaspora in the 1930s. The extraordinary flowering of

poetry in the Spanish language on both sides of the Atlantic had

next to no international impact until the Spanish Civil War of

1936-39 revealed it. Even the arts least hampered by the tower of

Babel, those of sight and sound, were less international than might

be supposed, as a comparison of the relative standing of, say,

Hindemith in and outside Germany or of Poulenc in and outside France

shows. Educated English art-lovers entirely familiar with even the

lesser members of the inter-war Ecole de Paris, might not even have

heard the names of German expressionist painters as important as

Nolde and Franz Marc.

There were really only two

avant-garde arts which all flag-carriers of artistic novelty in all

relevant countries could be guaranteed to admire, and both came out

of the new world rather than the old: films and jazz. The cinema was

co-opted by the avant-garde some time during the First World War,

having previously been unaccountably neglected by it. It not merely

became essential to admire this art, and notably its greatest

personality, Charlie Chaplin (to whom few self-respecting modern

poets failed to address a composition), but avant-garde artists

themselves launched themselves into film-making, most notably in

Weimar Germany and Soviet Russia, where they actually dominated

production. The canon of 'art-films' which the highbrow film-buffs

were expected to admire in small specialized movie-temples during

the age of cataclysms, from one side of the globe to the other,

consisted essentially of such avant-garde creations: Sergei

Eisenstein's (1898-1948) Battleship Potemkin of 1925 was generally

regarded as the all-time masterpiece. The Odessa Steps sequence of

this work, which no one who ever saw it - as I did in a Charing

Cross avant-garde cinema in the 1930s - will ever forget, has been

described as 'the classic sequence of silent cinema and possibly the

most influential six minutes in cinema history' (Manvell, 1944, pp.

47-48).

From the mid-1930s, intellectuals

favoured the populist French cinema of Rene Clair; Jean Renoir (not

uncharacteristically the painter's son); Marcel Carne; Prevert, the

ex-surrealist; and Auric, the ex-member of the avant-garde musical

cartel lLes Six\ These, as non-intellectual critics liked to point

out, were less enjoyable, though no doubt artistically more

high-class than the great bulk of what the hundreds of millions

(including the intellectuals) watched every week in increasingly

gigantic and luxuri-ous picture-palaces, namely the production of

Hollywood. On the other hand the hard-headed showmen of Hollywood

were almost as quick as Diaghilev to recognize the avant-garde

contribution to profitability. 'Uncle' Carl Laemmle, the boss of

Universal Studios, perhaps the least intellectually ambitious of

the Hollywood majors, took care to supply himself with the latest

men and ideas on his annual visits to his native Germany, with the

result that the characteristic product of his studios, the horror

movie (Frankenstein, Dracula etc.) was sometimes a fairly close copy

of German expressionist models. The flow of central-European

directors, like Lang, Lubitsch and Wilder, across the Atlantic - and

practically all of them can be regarded as highbrows in their native

grounds - was to have a considerable impact on Hollywood itself, not

to mention that of technicians like Karl Freund (1890-1969) or Eugen

Schufftan (1893-1977). However, the course of the cinema and the

popular arts will be considered below.

The 'jazz' of the 'Jazz Age', i.e. some kind of combination of

American Negroes, syncopated rhythmic dance-music and an

instrumentation which was unconventional by traditional standards,

almost certainly aroused universal approval among the avant-garde,

less for its own merits than as yet another symbol of modernity, the

machine age, a break with the past - in short, another manifesto of

cultural revolution. The staff of the Bauhaus had itself

photographed with a saxophone. A genuine passion for, the sort of

jazz which is now recognized as the major contribution of the USA to

twentieth-century music, remained rare among established

intellectuals, avant-garde or not, until the second half of the

century. Those who developed it, as I did after Duke Ellington's

visit to London in 1933, were a small minority.

Whatever the local variant of

modernism, between the wars it became the badge of those who wanted

to prove that they were both cultured and up to date. Whether or not

one actually liked, or even had read, seen or heard, works by the

recognized OK names - say, among literary English schoolboys of the

first half of the 1930s, T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, James Joyce and D.H.

Lawrence - it was inconceivable not to talk knowledgeably about

them. What is perhaps more interesting, each country's cultural

vanguard rewrote or revalued the past to fit in with contemporary

requirements. The English were firmly told to forget about Milton

and Tennyson, but to admire John Donne. The most influential British

critic of the period, F.R. Leavis of Cambridge, even devised a

canon, or 'great tradition', of English novels which was the exact

opposite of a real tradition, since it omitted from the historical

succession anything the critic did not like, such as all of Dickens,

with the exception of one novel hitherto regarded as one of the

master's minor works, Hard Times

For lovers of Spanish painting,

Murillo was now out, but admiration for El Greco was compulsory. But

above all, anything to do with the Age of Capital and the Age of

Empire (other than its avant-garde art) was not only rejected: it

became virtually invisible. This was not only demonstrated by the

vertical fall in the prices of nineteenth-century academic painting

(and the corresponding but still modest rise of the Impressionists

and later modernists): they remained practically unsaleable until

the 1960s. The very attempts to recognize any merit in Victorian

building had about them an air of deliberate provocation of real

good taste, associated with camp reactionaries. The present author,

grown up among the great architectural monuments of the liberal

bourgeoisie which encircle Vienna's old 'inner city', learned, by a

sort of cultural osmosis, that they were to be regarded as either

inauthentic or pompous or both. Such buildings were not actually

torn down en masse until the 1950s and 1960s, the most disastrous

decade in modern architecture, which is why a Victorian Society to

protect buildings of the 1840-1914 period was not set up in Britain

until 1958 (more than twenty years after a Georgian Group, to

protect the less outcast eighteenth-century heritage).

The impact of the avant-garde on

the commercial cinema already suggests that 'modernism' began to

make its mark on everyday life. It did so obliquely, through

productions which the broad public did not consider to be 'art', and

consequently to be judged by a priori criteria of aesthetic value:

primarily through publicity, industrial design, commercial print and

graphics, and genuine objects. Thus among champions of modernity

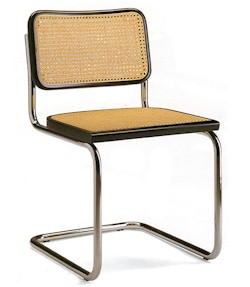

Marcel Breuer's (1902-81) famous tubular chair (1925—29) carried an

enormous ideological and aesthetic charge (Giedion, 1948, pp.

488-95). Yet it was to make its way through the modern world not as

a manifesto, but as the modest but universally useful movable

stacking chair.

But there can be no doubt at all that, within less

than twenty years of the outbreak of the First World War,

metropolitan life all over the Western world was visibly marked by

modernism, even in countries like the USA and Great Britain, which

appeared entirely unreceptive to it in the 1920s. Streamlining,

which swept through the American design of both suitable and

unsuitable products from the early 1930s, echoed Italian futurism.

The Art Deco style (derived from the Paris Exposition of Decorative

Arts of 1925) domesticated modernist angularity and abstraction. The

modern paperback revolution in the 1930s (Penguin Books) carried the

banner of the avant-garde typography of Jan Tschichold (1902-74).

The direct assault of modernism was still deflected. Not until after

the Second World War did the so-called International Style of

modernist architecture transform the city scene, though its chief

propagandists and practitioners - Gropius, Le Corbusier, Mies van

der Rohe, Frank Lloyd Wright, etc.- had long been active. Some

exceptions apart, the bulk of public building, including public

housing projects by municipalities of the Left, which might have

been expected to sympathize with the socially conscious new

architecture, showed little sign of its influence except an apparent

dislike for decoration. Most of the massive rebuilding of

working-class 'Red Vienna' in the 1920s was undertaken by architects

who figure barely, if at all, in most histories of architecture. But

the lesser equipment of everyday life was rapidly reshaped by

modernity.

How far this was due to the

heritage of the arts-and-crafts and art nouveau movements, in which

vanguard art had committed itself to daily use; how far to the

Russian constructivists, some of whom deliberately set out to

revolutionize mass production design; how far to the genuine

suitability of modernist purism for modern domestic technology (e.g.

kitchen design) we must leave to art history to decide. The fact

remains that a short-lived establishment, which began very much as a

political and artistic avant-garde centre, came to set the tone of

both architecture and the applied arts of two generations. This was

the Bauhaus, or art and design school of Weimar and later Dessau in

Central Germany (1919-33), whose existence coincided with the Weimar

Republic - it was dissolved by the National Socialists shortly after

Hitler took power. The list of names associated with the Bauhaus in

one way or another reads like a Who's Who of the advanced arts

between the Rhine and the Urals: Gropius and Mies van der Rohe;

Lyonel Feininger, Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky; Malevich, El

Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy, etc. Its influence rested not only on these

talents but - from 1921 - on a deliberate turn away from the old

arts-and-crafts and (avant-garde) fine arts tradition to designs for

practical use and industrial production: car bodies (by Gropius),

aircraft seats, advertising graphics (a passion of the Russian

constructivist El Lissitzky), not forgetting the design of the one

and two million Mark banknotes during the great German

hyper-inflation of 1923.

The Bauhaus - as its problems with

unsympathetic politicians shows — was considered deeply subversive.

And, indeed, political commitment of one kind or another dominates

the 'serious' arts in the Age of Catastrophe. In the 1930s it

reached even Britain, still a haven of social and political

stability amid European revolution, and the USA, remote from war but

not from the Great Slump. That political commitment was by no means

only to the Left, though radical art-lovers found it hard,

especially when young, to accept that creative genius and

progressive opinions should not go together. Yet, especially in

literature, deeply reactionary convictions, sometimes translated

into fascist practice, were common enough in Western Europe. The

poets T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound in Britain and exile; William Butler

Yeats (1865-1939) in Ireland; the novelists Knut Hamsun (1859-1952)

in Norway, an impassioned collaborator of the Nazis, D.H. Lawrence

(1885-1930) in Britain and Louis Ferdinand Celine in France

(1884-1961) are obvious examples. The brilliant talents of the

Russian emigration cannot, of course, be automatically classified as

'reactionary', although some of them were, or became, so; for a

refusal to accept Bolshevism united émigrés of widely different

political views.

Nevertheless, it is probably safe

to say that in the aftermath of world war and the October

revolution, and even more in the era of anti-fascism of the 1930s

and 1940s, it was the Left, often the revolutionary Left, that

primarily attracted the avant-garde. Indeed, war and revolution

politicized a number of notably non-political pre-war avant-garde

movements in France and Russia. (Most of the Russian avant-garde,

however, showed no initial enthusiasm for October.) As Lenin's

influence brought Marxism back to the Western world as the only

important theory and ideology of social revolution, so it assured

the conversion of avant-gardes to what the National Socialists, not

incorrectly, called 'cultural Bolshevism' (Kultur-bolschewismus).

Dada was for revolution. Its successor, surrealism, had difficulty

only in deciding which brand of revolution it was for, the majority

of the sect choosing Trotsky over Stalin. The Moscow-Berlin axis

which shaped so much of Weimar culture rested on common political

sympathies. Mies van der Rohe built a monument to the murdered

Spartacist leaders Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg for the German

Communist Party. Gropius, Bruno Taut (1880-1938), Le Corbusier,

Hannes Meyer and an entire 'Bauhaus Brigade' accepted Soviet

commissions - admittedly at a time when the Great Slump made the

USSR not merely ideologically but also professionally attractive to

Western architects. Even the basically not very political German

cinema was radicalized, as witness the wonderful director G.W. Pabst

(1885— 1967), a man visibly more interested in presenting women

rather than public affairs, and later quite prepared to work under

the Nazis. Yet in the last Weimar years he was the author of some of

the most radical films, including Brecht-Weill's Threepenny Opera.

It was the tragedy of modernist

artists, Left or Right, that the much more effective political

commitment of their own mass movements and politicians - not to

mention their adversaries - rejected them. With the partial

exception of Futurist-influenced Italian fascism, the new

authoritarian regimes of both Right and Left preferred old-fashioned

and gigantic monumental buildings and vistas in architecture,

inspirational representations in both painting and sculpture,

elaborate performances of the classics on stage, and ideological

acceptability in literature. Hitler, of course, was a frustrated

artist who eventually found a competent young architect to realize

his gigantic conceptions, Albert Speer. However, neither Mussolini

nor Stalin nor General Franco, all of whom inspired their own

architectural dinosaurs, began life with such personal ambitions.

Neither the German nor the Russian avant-garde, therefore, survived

the rise of Hitler and Stalin, and the two countries, spearhead of

all that was advanced and distinguished in the arts of the 1920s,

almost disappear from the cultural scene.

In retrospect we can see better

than contemporaries could what a cultural disaster the triumph of

both Hitler and Stalin proved to be, that is to say, how much the

avant-garde arts were rooted in the revolutionary soil of central

and eastern Europe. The best wine of the arts seemed to grow on the

lava-streaked slopes of volcanoes. It was not merely that the

cultural authorities of politically revolutionary regimes gave more

official recognition, i.e. material backing, to artistic

revolutionaries than the conservative ones they replaced, even if

their political authorities showed no enthusiasm. Anatol Lunacharsky,

the 'Commissar for Enlightenment', encouraged the avant-garde,

though Lenin's taste in the arts was quite conventional. The

social-democratic government of Prussia, before it was expelled in

1932 from office (unresistingly) by the authorities of the more

right-wing German Reich, encouraged the radical conductor Otto

Klemperer to turn one of the Berlin opera houses into a showcase of

all that was advanced in music between 1928 and 1931. However, in

some indefinable way, it also seems that the times of cataclysm

heightened the sensibilities, sharpened the passions of those who

lived through them, in Central and Eastern Europe. Theirs was a

harsh not a happy vision, and its very harshness and the tragic

sense that infused it was what sometimes gave talents which were not

in themselves outstanding a bitter denunciatory eloquence, for

instance B. Traven, an insignificant anarchist bohemian emigrant

once associated with the short-lived Munich Soviet Republic of 1919,

who took to writing movingly about sailors and Mexico (Huston's

Treasure of the Sierra Madre with Bogart is based on him). Without

it he would have remained in deserved obscurity. Where such an

artist lost the sense that the world was intolerable, as the savage

German satirist George Grosz did on emigrating to the USA after

1933, nothing remained but technically competent sentimentality.

The central European avant-garde

art of the Age of Cataclysm rarely articulated hope, even though its

politically revolutionary members were committed to an upbeat vision

of the future by their ideological convictions. Its most powerful

achievements, most of them dating from the years before Hitler's and

Stalin's supremacy - 'I can't think what to say about Hitler',

quipped the great Austrian satirist Karl Kraus, whom the First World

War had left far from speechless (Kraus, 1922) - come out of

apocalypse and tragedy: Alban Berg's opera Wozzek (first performed

1926); Brecht and Weill's Threepenny Opera (1928) and Mahagonny

(1931); Brecht-Eisler's Die Massnahme (1930); Isaac Babel's stories

Red Cavalry (1926); Eisenstein's film Battleship Potemkin (1925); or

Alfred Doblin's Berlin-Alexanderplatz (1929). As for the collapse of

theHabsburg Empire, it produced an extraordinary outburst of

literature, ranging from the denunciation of Karl Kraus's The Last

Days of Humanity (1922) through the ambiguous buffoonery of Jaroslav

Hasek's Good Soldier Schwejk (1921) to the melancholy threnody of

Josef Roth's Radetskymarsch (1932) and the endless self-reflection

of Robert Musil's Man without Qualities (1930). No set of political

events in the twentieth century has had a comparably profound impact

on the creative imagination, although in their own ways the Irish

revolution and civil war (1916— 22) through O'Casey and, in a more

symbolic mode, through its muralists, the Mexican revolution

(1910—20) - but not the Russian revolution -inspired the arts in

their respective countries. An empire destined to collapse as a

metaphor for a Western elite culture itself undermined and

collapsing: these images had long haunted the dark corners of the

Central European imagination. The end of order found expression in

the great poet Rainer Maria Rilke's (1875-1926) Duino Elegies

(1913-23). Another Prague writer in the German language presented an

even more absolute sense of the incomprehensibility of the human

predicament, both singular and collective: Franz Kafka (1883-1924),

almost all of whose work was published posthumously. This, then, was

art created

in the days the world was falling

the

hour the earth's foundations fled

to cite the classical scholar and

poet A.E. Housman, who was far from the avant-garde (Housman, 1988,

p. 138). This was art whose view was that of the 'angel of history',

whom the German-Jewish marxist Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) claimed

to recognize in Paul Klee's picture Angelus Novus:

His face is turned towards the

past. Where we see a chain of events before us, he sees a single

catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon ruin till they reach

his feet. If only he could stay to wake the dead and to piece

together the fragments of what has been broken! But a storm blows

from the direction of Paradise, catching his wings with such force

that the Angel can no longer close them. This storm drives him

irresistibly into the future, to which his back is turned, while the

pile of debris at his feet grows into the sky. This storm is what we

call progress (Benjamin, 1971, pp. 84-85).

West of the zone of collapse and

revolution the sense of a tragic and ineluctable cataclysm was less,

but the future seemed equally enigmatic. In spite of the trauma of

the First World War, continuity with the past was not so obviously

broken until the 1930s, the decade of the Great Slump, fascism and

the steadily approaching war. (Indeed, the major literary echoes of

the First World War only began to reverberate towards the end of the

1920s when Erich Maria Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front

(1929, Hollywood film 1930) sold two-and-a-half million copies in

eighteen months in twenty-five languages.) Even so, in

retrospect the mood of the Western intellectuals seems less

desperate and more hopeful than that of the central Europeans, now

scattered and isolated from Moscow to Hollywood, or the captive East

Europeans silenced by failure and terror. They still felt themselves

to be defending values threatened, but not yet destroyed, to

revitalize what was living in their society, if need be by

transforming it. As we shall see, much of the Western blindness to

the faults of the Stalinist Soviet Union was due to the conviction

that, after all, it represented the values of the Enlightenment

against the disintegration of reason; of 'progress' in the old and

simple sense, so much less problematic than Walter Benjamin's 'wind

blowing from Paradise'. It was only among ultra-reactionaries that

we find the sense of the world as an incomprehensible tragedy, or

rather, as in the greatest British novelist of the period, Evelyn

Waugh (1903-66), as a black comedy for stoics; or, as in the French

novelist Louis Ferdinand Celine (1894—1961), a nightmare even for

cynics. Though the finest and most intelligent of the young British

avant-garde poets of the time, W.H. Auden (1907—73), had a sense of

history as tragedy — Spain, Musee des Beaux Arts — the mood of the

group of which he was the centre found the human predicament

acceptable enough. The most impressive British artists of the

avant-garde, the sculptor Henry Moore (1898-1986) and the composer

Benjamin Britten (1913—76), give the impression that they would have

been quite ready to let the world crisis pass them by, had it not

intruded. But it did.

The avant-garde arts were still a

concept confined to the culture of Europe and its outliers and

dependencies, and even there the pioneers on the frontier of

artistic revolution still often looked longingly at Paris and even —

to a lesser but surprising extent — at London. It did not yet look

to New York. What this means is that the non-European avant-garde

barely existed outside the western hemisphere, where it was firmly

anchored to both artistic experiment and social revolution. Its

best-known representatives at this time, the mural painters of the

Mexican revolution, disagreed only about Stalin and Trotsky, but not

about Zapata and Lenin, whom Diego Rivera (1886-1957) insisted on

including in a fresco destined for the new Rockefeller Center in New

York (a triumph of art-deco second only to the Chrysler Building) to

the displeasure of the Rockefellers.

Yet for most artists in the

non-Western world the basic problem was modernity not modernism. How

were their writers to turn spoken vernaculars into flexible and

comprehensive literary idioms for the contemporary world, as the

Bengalis had done since the mid-nineteenth century in India? How

were men (perhaps, in these new days, even women) to write poetry in

Urdu, instead of the classical Persian hitherto obligatory for such

purposes; in Turkish instead of in the classical Arabic which

Ataturk's revolution threw into the dustbin of history with the fez

and the woman's veil? What, in countries of ancient cultures, were

they to do with or about their traditions; arts which, however

attractive, did not belong to the twentieth century? To abandon the

past was revolutionary enough to make the Western revolt of one

phase of modernity against another appear irrelevant or even

incomprehensible. All the more so when the modernizing artist was at

the same time a political revolutionary, as was more than likely.

Chekhov and Tolstoy might seem more apposite models than James Joyce

for those who felt their task — and their inspiration — was to 'go

to the people' and to paint a realistic picture of their sufferings

and to help them rise. Even the Japanese writers, who took to

modernism from the 1920s (probably through contact with Italian

Futurism), had a strong and from time to time dominant socialist or

communist 'proletarian' contingent (Keene, 1984, chapter 15).

Indeed, the first great Chinese modern writer, Lu Hsun (1881-1936),

deliberately rejected Western models and looked to Russian

literature where 'we can see the kindly soul of the oppressed, their

sufferings and struggles' (Lu Hsun, 1975, p. 23).

For most of the creative talents

of the non-European world who were neither confined within their

traditions nor simple Westernizers, the major task seemed to be to

discover, to lift the veil from, and to present the contemporary

reality of their peoples. Realism was their movement. In a way, this

desire united the arts of East and West. For the twentieth century,

it was increasingly clear, was the century of the common people, and

dominated by the arts produced by and for them. And two linked

instruments made the world of the common man visible as never before

and capable of documentation: reportage and the camera. Neither was

new (see Age of Capital, chapter 15; Age of Empire, chapter 9) but

both entered a self-conscious golden age after 1914. Writers,

especially in the USA, not only saw themselves as recorders or

reporters, but wrote for newspapers and indeed were or had been

newspapermen: Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961), Theodore Dreiser

(1871-1945), Sinclair Lewis (1885-1951). 'Reportage' - the term

first appears in French dictionaries in 1929 and in English ones in

1931 - became an accepted genre of socially-critical literature and

visual presentation in the 1920s, largely under the influence of the

Russian revolutionary avant-garde who extolled fact against the pop

entertainment which the European Left had always condemned as the

people's opium. The Czech communist journalist Egon Erwin Kisch, who

gloried in the name of 'Reporter in a Rush' (Der rasende Reporter,

1925, was the title of the first of a series of his reportages)

seems to have given the term currency in central Europe. It spread,

mainly via the cinema, through the Western avant-garde. Its origins

are clearly visible in the sections headed* 'Newsreel' and 'the

Camera Eye' - an allusion to the avant-garde film documentarist

Dziga Vertov - with which the narrative is intercut in John Dos

Passos' (1896— 1970) trilogy USA, written in that novelist's

Left-wing period. In the hands of the avant-garde Left 'documentary

film' became a self-conscious movement, but in the 1930s even the

hard-headed professionals of the news and magazine business claimed

a higher intellectual and creative status by upgrading some movie

newsreels, usually undemanding space-fillers, into the more

grandiose 'March of Time' documentaries, and borrowing the technical

innovations of the avant-garde photographers as pioneered in the

communist AIZ of the 1920s to create a golden age of the

picture-magazine: Life in the USA, Picture Post in Britain, Vu in

France. However, outside the Anglo-Saxon countries it only began to

flourish massively after the Second World War.

The new photo-journalism owed its

merits not only to the talented men - even some women - who

discovered photography as a medium, to the illusory belief that 'the

camera cannot lie', i.e. that it somehow represented 'real' truth,

and to the technical improvements that made unposed pictures easy

with the new miniature cameras (the Leica launched in 1924), but

perhaps most of all to the universal dominance of the cinema. Men

and women learned to see reality through camera lenses. For while

there was growth in the circulation of the printed word (now also

increasingly interwoven with rotogravure photos in the tabloid

press), it lost ground to the film. The Age of Catastrophe was the

age of the large cinema screen. In the late 1930s for every British

person who bought a daily newspaper, two bought a cinema ticket

(Stevenson, pp. 396, 403). Indeed, as depression deepened and the

world was swept by war, Western cinema attendances reached their

all-time peak.

In the new visual media,

avant-garde and mass arts fertilized one another. Indeed, in the old

Western countries the domination of the educated strata and a

certain elitism penetrated even the mass medium of film, producing a

golden age for the German silent film in the Weimar era, for the

French sound film in the 1930s, and for the Italian film as soon as

the blanket of fascism which covered its talents had been lifted. Of

these perhaps the populist French cinema of the 1930s was most

successful in combining what intellectuals wanted from culture with

what the larger public wanted from entertainment. It was the only

highbrow cinema which never forgot the importance of the story,

especially about love and crime, and the only one capable of making

good jokes. Where the avant-garde (political or artistic) had its

own way entirely, as in the documentary movement or agitprop art,

its work rarely reached beyond small minorities.

However, the avant-garde input is

not what makes the mass arts of the period significant. It is their

increasingly undeniable cultural hegemony even though, as we have

seen, outside the USA they still had not quite escaped from the

supervision of the educated. The arts (or rather entertainments)

which became dominant were those aimed at the broadest masses rather

than at the large, and growing, middle-class and lower-middle class

public with traditional tastes. These still dominated the European

'boulevard' or 'West End' stage or its equivalents, at least until

Hitler dispersed the manufacturers of such products, but their

interest is slight. The most interesting development in this

middlebrow region was the extraordinary, explosive growth of a genre

that had shown some signs, of life before 1914, but no hint of its

subsequent triumphs: the detective puzzle story, now mainly written

at book-length. The genre was primarily British - perhaps a tribute

to A. Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes, who became internationally

known in the 1890s - and, more surprisingly, largely female or

academic. Its pioneer, Agatha Christie (1891-1976) remains a

bestseller to this day. The international versions of this genre

were still largely, and evidently, inspired by the British model,

i.e. they were almost exclusively about murder treated as a parlour

game requiring some ingenuity, rather like the high-class crossword

puzzles with enigmatic clues which were an even more exclusively

British speciality. The genre is best seen as a curious invocation

to a social order threatened but not yet breached. Murder, which now

became the central, almost the only crime to mobilize the detective,

irrupts into a characteristically ordered environment - the country

house, or some familiar professional milieu - and is traced to one

of those rotten apples which confirm the soundness of the rest of

the barrel. Order is restored through reason as applied to the

problem by the detective who himself (he was still overwhelmingly

male) represents the milieu. Hence perhaps the insistence on the

private investigator, unless the policeman himself is, unlike most

of his kind, a member of the upper and middle classes. It was a

deeply conservative, though still self-confident genre, unlike the

contemporary rise of the more hysterical secret agent thriller (also

mainly British), a genre with a great future in the second half of

the century. Its authors, men of modest literary merits, often found

a suitable metier in their country's secret service.(The literary

ancestors of the modern 'hard-boiled' thriller or 'private eye'

story were much more demotic. Dashiell Hammett (1894-1961) began as

a Pinkerton operative and published in pulp magazines. For that

matter the only writer to turn the detective story into genuine

literature, the Belgian Georges Simenon (1903-89), was an autodidact

hack writer.)

By 1914 mass media on the modern

scale could already be taken for granted in a number of Western

countries. Nevertheless, their growth in the age of cataclysms was

spectacular. Newspaper circulation in the USA rose much faster than

population, doubling between 1920 and 1950. By that time something

between 300 and 350 papers were sold for every 1,000 men, women and

children in the typical 'developed' country, though the

Scandinavians and Australians consumed even more newsprint, and the

urbanized British, possibly because their press was national rather

than localized, bought an astonishing six hundred copies per

thousand of the population (UN Statistical Yearbook, 1948). The

press appealed to the literate, although in countries of mass

schooling it did its best to satisfy the incompletely literate by

means of pictures and comic strips, not yet admired by the

intellectuals, and by developing a highly-coloured,

attention-grabbing, pseudo-demotic idiom avoiding words of too many

syllables. Its influence on literature was not negligible. The

cinema, on the other hand, made small demands on literacy, and after

it learned to talk in the late 1920s, practically none on the

English-speaking public.

However, unlike the press, which

in most parts of the world interested only a small elite, films were

almost from the start an international mass medium. The abandonment

of the potentially universal language of the silent film with its

tested codes for cross-cultural communication probably did much to

make spoken English internationally familiar and thus helped to

establish the language as the global pidgin of the later twentieth

century. For, in the golden age of Hollywood, films were essentially

American — except in Japan, where about as many full-size movies

were made as in the USA. As for the rest of the world, on the eve of

the Second World War Hollywood produced about as many films as all

other industries combined, even if we include India which already

produced about 170 a year for an audience as large as Japan's and

almost as large as the USA's. In 1937 it turned out 567 films, or

rather more than ten a week. The difference between the hegemonic

capacity of capitalism and bureaucratized socialism is that between

this figure and the forty-one films the USSR claimed to have

produced in 1938. Nevertheless, for obvious linguistic reasons, so

extraordinary a global predominance of a single industry could not

last. In any case it did not survive the disintegration of the

'studio system' which reached its peak in this period as a machine

for mass-producing dreams, but collapsed shortly after the Second

World War.

The third of the mass media was

entirely new: radio. Unlike the other two, it rested primarily on

the private ownership of what was still a sophisticated piece of

machinery, and was thus confined essentially to the comparatively

prosperous 'developed' countries. In Italy the number of radio sets

did not exceed that of automobiles until 1931 (Isola, 1990). The

greatest densities of radio-sets were to be found, on the eve of the

Second World War, in the USA, Scandinavia, New Zealand and Britain.

However, in such countries it advanced at a spectacular rate, and

even the poor could afford it. Of Britain's nine million sets in

1939, half had been bought by people earning between £2.5 and £4 per

week - a modest income - and another two million by people earning

less than this (Briggs, II, p. 254). It is perhaps not surprising

that the radio audience doubled in the years of the Great Slump,

when its rate of growth was faster than before or later. For radio

transformed the life of the poor, and especially of housebound poor

women, as nothing else had ever done. It brought the world into

their room. Henceforth the loneliest need never again be entirely

alone. And the entire range of what could be said, sung, played or

otherwise expressed in sound, was now at their disposal. Is it

surprising that a medium unknown when the First World War ended had

captured ten million households in the USA by the year of the stock

exchange crash, over twenty-seven millions by 1939, over forty

millions by 1950?

Unlike film, or even the

revolutionized mass press, radio did not transform the human ways of

perceiving reality in any profound way. It did not create new ways

of seeing or establishing relations between sense impressions and

ideas (see Age of Empire). It was merely the medium, not the

message. But its capacity for speaking simultaneously to untold

millions, each of whom felt addressed as an individual, made it an

inconceivably powerful tool of mass information and, as both rulers

and salesmen immediately recognized, for propaganda and

advertisement. By the early 1930s the President of the USA had

discovered the potential of the radio 'fireside chat', and the king

of Britain that of the royal Christmas broadcast (1932 and 1933

respectively). In the Second World War, with its endless demand for

news, radio came into its own as a political instrument and as a

medium of information. The number of radio sets in continental

Europe increased substantially in all countries except some of the

worst victims of battle (Briggs, III, Appendix C). In several cases

it doubled or more than doubled. In most of the non-European

countries the rise was even steeper. Commerce, though from the start

it ruled the airwaves over the USA, had a harder conquest elsewhere,

since by tradition governments were reluctant to give up control

over so powerful a medium for influencing citizens. The BBC

maintained its public monopoly. Where commercial broadcasting was

tolerated, it was nevertheless expected to defer to the official

voice.

It is difficult to recognize the

innovations of radio culture, since so much that it pioneered has

become part of the furniture of everyday life -the sports

commentary, the news bulletin, the celebrity guest show, the soap

opera, or indeed the serial programme of any kind. The most profound

change it brought was simultaneously to privatize and to structure

life according to a rigorous timetable, which henceforth ruled not

only the sphere of labour but that of leisure. Yet curiously this

medium - and, until the rise of video and VCR its successor,

television -though essentially centered on individual and family,

created its own public sphere. For the first time in history people

unknown to each other who met knew what each had in all probability

heard (or, later, seen) the night before: the big game, the

favourite comedy show, Winston Churchill's speech, the contents of

the news bulletin.

The art most significantly

affected by radio was music, since it abolished the acoustic or

mechanical limitations on the range of sounds. Music, the last of

the arts to break out of the bodily prison that confines oral

communication, had already entered the era of mechanical

reproduction before 1914 with the gramophone, although this was

hardly yet within reach of the masses. The years between the wars

certainly brought both gramophones and records within the range of

the masses, though the virtual collapse of the record-market for

'race records', i.e. typical poor people's music during the American

slump, demonstrates the fragility of this expansion. Yet the record,

though its technical quality improved after about 1930 had its

limits, if only of length. Moreover, its range depended on its

sales. Radio, for the first time, enabled music to be heard at a

distance at more than five minutes' unbroken length, and by a

theoretically limitless number of listeners. It thus became both a

unique popularizer of minority music (including classical music) and

by far the most powerful means for selling records, as indeed it

still remains. Radio did not change music - it certainly affected it

less than the theatre or the movies, which also soon learned to

reproduce sound - but the role of music in contemporary life, not

excluding its role as aural wallpaper for everyday living, is

inconceivable without it.

The forces which dominated the

popular arts were thus primarily technological and industrial:

press, camera, film, record and radio. Yet since the later

nineteenth century an authentic spring of autonomous creative

innovation had been visibly welling up in the popular and

entertainment quarters of some great cities (see Age of Empire). It

was far from exhausted, and the media revolution carried its

products far beyond their original milieus. Thus the Argentine tango

formalized, and especially amplified from dance into song, probably

reached its peak of achievement and influence in the 1920s and

1930s, and when its greatest star Carlos Gardel (1890-1935) died in

an air crash in 1935, he was mourned all over Spanish America, and

(thanks to records) turned into a permanent presence. The samba,

destined to symbolize Brazil as the tango did Argentina, is the

child of the democratization of the Rio carnival in the 1920s.

However, the most impressive and, in the long run, influential

development of this sort was the development of jazz in the USA,

largely under the impact of the migration of Negroes from the

southern states to the big cities of middle west and north-east: an

autonomous art music of professional (mainly black) entertainers.

The impact of some of these

popular innovations or developments was as yet restricted outside

their native milieus. It was also as yet less revolutionary than it

became in the second half of the century, when - to take the obvious

example — an idiom directly derived from the American Negro blues

became, as rock-and-roll, a global language of youth culture.

Nevertheless, though — with the exception of film - the impact both

of mass media and popular creation was more modest than it became in

the second half of the century (this will be considered below); it

was already enormous in quantity and striking in quality, especially

in the USA which began to exercise an unchallengeable hegemony in

these fields, thanks to its extraordinary economic preponderance,

its firm commitment to commerce and democracy and, after the Great

Slump, the influence of Rooseveltian populism. In the field of

popular culture the world was American or it was provincial. With

one exception, no other national or regional model established

itself globally, though some had substantial regional influence (for

instance, Egyptian music within the Islamic world) and an occasional

exotic touch entered global commercial popular culture from time to

time, as in the Caribbean and Latin American components of

dance-music. The unique exception was sport. In this branch of

popular culture - and who, having seen the Brazilian team in its

days of glory will deny it the claim to art? - US influence remained

confined to the area of Washington's political domination. As

cricket is played as a mass sport only where once the Union Jack

flew, so baseball made little impact except where US marines had

once landed. The sport the world made its own was association

football, the child of Britain's global economic presence, which had

introduced teams named after British firms,or composed of expatriate

Britons (like the Sao Paulo Athletic Club) from the polar ice to the

Equator. This simple and elegant game, unhampered by complex rules

and equipment, and which could be practised on any more or less flat

open space of the required size, made its way through the world

entirely on its merits and, with the establishment of the World Cup

in 1930 (won by Uruguay) became genuinely international.

And yet, by our standards, mass

sports, though now global, remained extraordinarily primitive. Their

practitioners had not yet been absorbed by the capitalist economy.

The great stars were still amateurs, as in tennis (i.e. assimilated

to traditional bourgeois status), or professionals paid a wage not

all that much higher than a skilled industrial worker's, as in

British football. They had still to be enjoyed face-to-face, for

even radio could only translate the actual sight of the game or race

into the rising decibels of a commentator's voice. The age of

television and sportsmen paid like filmstars was still a few years

away. But, as we shall see not all that many.