|

S5 History |

Last

update -

04 May 2023 |

Official European

School History 4-5 Syllabus:

English,

French,

German. |

|

|

|

Unit 6 - Nationalism in the 19th Century |

|

1. Socio-economic factors – Industrial Revolution

2. Cultural factors – Nationalism

3. Political military factors – War

Socio-economic factors

As we have seen,

the Industrial Revolution transformed the economic basis of

society with enormous social consequences. The old ruling

classes, the great land-owners were under pressure from the new

rising middle classes – the industrialists – to reorganise the

country politically.

Giving the industrialists a say in how the country was run,

would allow them to reorganise the country in the interests of

industry. This meant encouraging free trade, allowing the free

movement of people and ending feudal obligations and ties. It

meant in brief, liberalism. In much of Europe, people were often

either under the feudal control of small feudal states (as in

Germany) or the feudal control of foreign empires (such as the

Austrian Hapsburgs or Russian Romanovs).

|

|

|

|

A German cartoon of 1834

pokes fun at the large numbers of customs barriers in

pre-united Germany |

|

Either way, if capitalism was to develop,

these inefficient economic systems would have to change. As Marx

and Engels argued:

‘The necessary consequence of this was political centralisation.

Independent, or but loosely connected provinces, with separate

interests, laws, governments, and systems of taxation, became

lumped together into one nation, with one government, one code

of laws, one national class-interest, one frontier, and one

customs-tariff.’ Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels:

The Communist Manifesto (1848)

|

|

|

Above left the 'German'

rail network in 1850, before unification and above right

in 1870. |

Cultural factors

And of course the development of industrial capitalism not only

required the creation of nation states, capitalism also made it

possible. By the late 19th century, subjects of monarch had

become citizens with a democratic stake in the future direction

of society. Individuals had lost their traditional peasant

attachments and village loyalties as they were urbanised,

educated and introduced to the ‘imagined communities’ and

‘invented traditions’ of the new nation states. They read their

daily national newspapers in codified national languages,

attended new schools with state directed national curricula,

travelled across their nation on national railway networks and

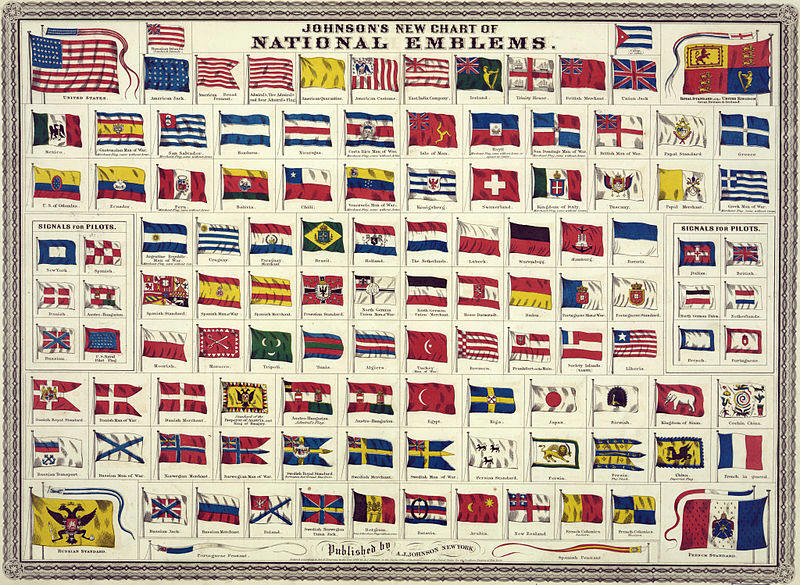

went to war waving newly invented flags (see Johnson's chart

below from 1867), singing newly composed

anthems.

|

|

In a time when the church and

feudal ties were being weakened, nationalism, as the German

philosopher Hegel pointed out, was a useful way giving people a

sense of belonging and something to be loyal to. Nationalism

became the cultural glue that bound society together.

Where the nation states did not yet exist,

nationalists set out to create them. Popular movements like

Young Italy and Young Ireland, inspired by Romantic philosophy

and literature, established the principal characteristic

features of the nation and campaigned politically for its

creation.

Romanticism was a reaction to the Enlightenment that

emphasised not human rationalism, but rather human emotion.

Romantic artists and poets contrasted the beauty of wild nature

to the ugliness of the new cities. Romanticism and nationalism

shared a longing for an idealised past.

Romantic nationalism and rational liberalism

were therefore very different responses to the Industrial

Revolution. Liberals and nationalists were only united in their

opposition to feudalism. Where opposition from conservatives was

fierce, revolution was said to provide the answer. In 1830 and

1848 throughout Europe, nationalists and liberals fought

together establish their new political forms.

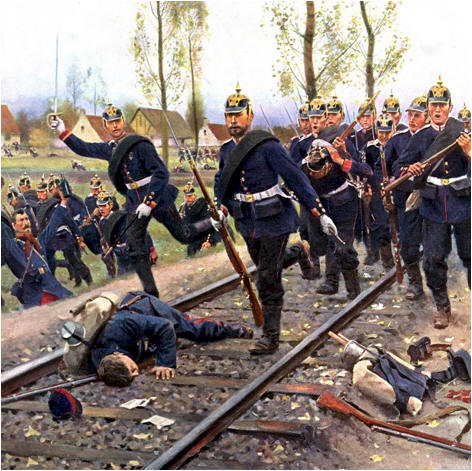

War

But whilst the revolutionaries remained fundamentally divided

and weak national ambitions failed. In the end, the great nation

building of the 19th century came about as a consequence of war.

New nationalist sentiment and industrial expediency encouraged

new nation states to be willed, but old fashioned power politics

and military conquest made it possible for them to be created.

Industrial development allowed Prussia to challenge the

political hegemony of Austria and France in the wars of

unification in the 1860s. |

|

|

‘Since the treaties of

Vienna, our frontiers have been ill-designed for a

healthy body politic. Not through speeches and majority

decisions will the great questions of the day be decided

- that was the great mistake of 1848 and 1849 - but by

iron and blood.’ Otto von Bismarck (1862). |

|

|

|

|