|

Relics are holy objects associated with holy

people such as Jesus or the saints. The use of relics was by no means a new phenomenon, it existed

previously in Judaism, Buddhism and several other religions.

In a world where people believed that evil and

the Devil existed all around in the natural world, it was comforting to

believe that good was also something that could be seen and touched. The

motivation

for most pilgrimages was to see and touch something holy and consequently benefit from being in contact with good. Two

types of relic

|

There are two types of

relic. The first kind were called brandea and were the most

common kind of early Christian relic in the centuries immediately following

the death of Christ. These were often ordinary objects which had become holy

by coming into contact with holy people or places. These might include, for

example, pieces of tomb, a handkerchief of a saint or dust from the

Holy Land.The advantage for pilgrims

was that they could and did make their own brandea; by rubbing

a piece of cloth against a holy tomb or by filling a small flask (ampulla)

with holy water, they could take the holiness home with them. In the 6th

century, Gregory of Tours described how this might be done at the tomb of St

Peter: |

| (Above) Flasks

(ampulla) made from lead were an important form of pilgrim souvenirs. They

would be filled with Holy Water at a shrine, such as Canterbury

in England. Holy Water was believed to heal the sick. (source) |

|

'He who wishes to pray

before the tomb opens the barrier that surrounds it and puts his head

through a small opening in the shrine...Should he wish to bring back a relic

from the tomb, he carefully weighs a piece of cloth which he then hangs

inside the tomb. Then he prays ardently and, if his faith is sufficient, the

cloth, once removed from the tomb, will be found to be so full of divine

grace that it will be much heavier than before.' (Sumption: 24)

These early relics were

often carried in small, purpose built containers called reliquaries which

were hung around the neck, almost like good luck charms. Of course, medieval

people did not believe in luck, they believed that God controlled everything

(see Church). Therefore, by wearing the relic you

were showing you believed in the Christian faith and consequently you hoped

God would reward you by making good things happen.

| The second kind

of relic which became common after the 7th century were bodily

relics, these were actual pieces of the body of the saint: a bone,

a piece of hair, the head etc. The Church initially outlawed the

movement of the body of a saint from the original burial place but

over time both the movement (translation) and dividing up (partition)

of the body of a saint was allowed. Two factors explain the spread of

relics all over Europe from the 8th century. Firstly, after 787 all

new Christian churches had to have a relic before they could be

properly established or 'consecrated'. During this time, much of

northern Europe was being converted to Christianity and there were

many new churches that required relics. As a consequence, the Church

partitioned and translated a portion of her collection all over

Europe. The second factor which explains the spread of relics was the

value placed on them by influential collectors all over Europe. Owning

a large number of relics became a symbol of status and power for both

private collectors and kingdoms. Emperor Charlemagne (742-814) set a

trend with his massive collection at Aachen that later monarchs of

Europe tried to follow. |

|

|

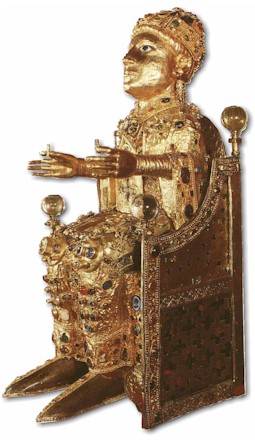

(Above) Charlemagne's

Reliquary at Aachen |

The craze to collect relics

even gave rise to national rivalries. When in 1244, Westminster Abbey received

the relic of a vase of the blood of Christ, the Bishop of Norwich made a

direct and unfavourable comparison to the recent purchase of part of the

True Cross by the King of France, Louis IX. He argued with impeccable

politician's logic:

'Now it is true that the

Cross is a very holy relic but it is holy because it came into contact with

the precious blood of Christ. The holiness of the Cross derives from the

blood whereas the holiness of the blood in no way derives from the Cross. It

therefore follows that England, which possesses the blood of Christ,

rejoices in a greater treasure than France, which has no more than the

Cross.' (Sumption: 30-1)

| Bodily relics were

particularly important because the spirit of the saint was said to actually

remain in the bodily remains. Wherever the body (or body parts) went the

(holy) spirit was sure to follow. There were some religious critics who

suggested that the cult of relics owed more to pagan traditions than

Christian teaching, but such was the popularity of the relics and the

miracles that surrounded them, it would have been very difficult for the

Church to resist even if it had wanted to. In converting pagan people the

Church needed every trick in the book. In the 13th century, even the great

medieval philosopher and saint, Thomas Aquinas, produced a threefold defence

of the cult of relics. He argued that, firstly, the relic acts as a physical

reminder of the saint, making it easier for people to understand the

importance of the saint. Secondly, because the saint worked miracles through

the body, the body remains holy and is therefore valuable in itself.

Finally, because miracles occur at sites with relics, God must approve of

the preservation and worship of relics. |

|

|

(above) The foot

reliquary of St James, Namur, France |

The relic business:

faking and thieving

When the church began to

allow the partition and translation of relics, the business of trading in

relics began to take off. Even before this time there were many

professionals who made a living out of buying and selling relics. Since it was extremely hard to verify the authenticity of the relics

(there were no DNA-tests or carbon-14 tests in the Middle Ages!) the trade was a

goldmine for all fakers and forgers. This

was particularly the case after 1204, when the fourth Crusade captured

Constantinople, which had perhaps the largest collection of relics in Christendom. The

Constantinople relics found their way into churches all over Europe.

The only way of

guaranteeing yourself a widely acknowledged, 'authentic' relic was to steal

one. Many of the most famous pilgrimage sites in Europe included stolen

relics in their collection. The theft was easily justified. Often the idea

for the theft came in the form of a dream or vision, which was widely

considered to be the way God and saints communicated . Often the saint

itself decided. If the saint allowed itself to be taken without punishing

the thieves and if the saint continued to produce miracles, then clearly he

or she was happy in their new home.

But there was only really a problem for the Church when two shrines

claimed to have the same relic (in the 11th century, there were at least

three heads of John the Baptist in circulation and this was true of a number

of equally 'unique' relics) or when a church claimed to have a relic of

obviously questionable validity. This was particularly the case with bodily

relics of Christ. His adult body was, of course, resurrected to heaven,

leaving no bones for collectors to hoard. But there were parts of his body

separated from his body, that did remain on earth. There were multiple

copies of everything imaginable, from umbilical cords, to milk teeth, all

over Europe.

In the 11th century, the popes' private chapels in Rome contained the

umbilical cord and foreskin of Christ in a gold and jewelled crucifix and

preserved in oil, along with the following impressive list of relics: a

piece of the true cross, the heads of the saints Peter and Paul, the ark of

the covenant, the tablets of Moses, the rod of Aaron, a golden urn of manna,

the tunic of the Virgin, various pieces of clothing worn by John the Baptist

including his hair shirt, the five loaves and two fishes which fed the five

thousand and the table used at the Last Supper. (Sumption: 222-3) Relics

were big business!

Reliquaries

|

|

As long as a relic was

never moved or never stolen, there was less of a problem in guaranteeing the

authenticity of the relic. In 1215, the Church decided that to minimize

theft, all relics should be stored and displayed in a special box, a

'reliquary'. In 1255, it was further decided that under no account should

relics be removed from reliquaries. Reliquaries had

existed long before the 13th century. The earliest reliquaries of

body-relics reflected the belief that the medieval belief that the

saint actually inhabited the church where their relics were kept.

These statue-reliquaries originated in southern France in the 10th

century. The statue of St. Foy in Conques is a particularly good

example. It is made of gold and is covered in precious stones. (see

left)

It illustrates the extent to which

churches were prepared to compete with rival pilgrimage sites.

Pilgrims expected to be impressed by the quality of the reliquary. If

a reliquary was beautifully made by the finest craftsmen, out of the

most precious materials, it not only represented the power of the

saint, it also meant that lots of previous pilgrims had been impressed

with the saint's power. The tomb of St. Thomas of Canterbury was

completed at enormous expense in 1220. When Henry VIII closed the

monasteries during the English Reformation, the jewels and precious

metals from the tomb of St. Thomas alone filled 26 carts!

|

|

(above) Statue-reliquary

of St. Foy at Conques, France |

Other religious memorabilia

|

Apart from the relics and magnificent

reliquaries, the pilgrimage churches found other ways to commemorate

the miracles of their saints. Artists might be commissioned to paint

murals on the walls of the church that described the story of the

saints. Churches also had sculptures and tapestries that told the

stories of the miracles. In a society where few could read or write,

pictorial communication was vital. |

|

|

|

(Above) A detail

from Bourges cathedral France showing the Last Judgement. |

Many of artistic riches of the churches

came from grateful pilgrims as offerings of their thanks. Perhaps

the strangest way of thanking the saint, involved the pilgrim making a

wax model to represent the part of the body that had been miraculously

healed. Churches encouraged this tradition because, as with the

magnificent reliquaries, the exhibited wax body parts were proof of

previous miracles. Sometimes these offerings of proof could be a

little bit gory: Henry of Maldon's tapeworm was hung on the altar

of Canterbury cathedral, alongside a real finger of the shepherd

who hoped that St. Thomas would help him grow another!

In general, shrines expected to receive more useful offerings from

their pilgrims. Pilgrims were expected to offer as much money or

jewels as they could afford. The miracle stories were full of accounts

which told of the dreadful consequences of failing to be appropriately

generous. One

lady pilgrim who left the basilica of Conques with a valuable ring on

her finger, became suddenly ill and was only cured when the monks

thoughtfully removed the ring and placed it in their treasury.

| Perhaps

the most famous of this type of story concerned Sir Jordan Fitz- Eisulf; a

story told through the stained class at Canterbury (see right). Having been saved

from the plague by drinking the holy water of St Thomas, Fitz-Eisulf

collected four silver coins as an offering to the saint. When he

failed to give the coins to the shrine as promised, the plague returned and killed his

oldest son. In the stained glass, Fitz-Eisulf can be seen pouring a

big sack, full of coins over the shrine. |

|

|

(Above) St Thomas

appears from above spreading the plague amongst the family of

Fitz-Eisulf. |

|

|