The nature of the Empire

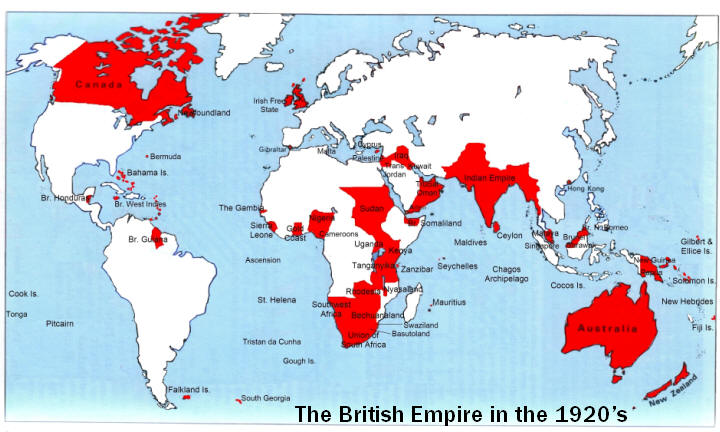

The Versailles

Settlement after the First World War made the British Empire

even larger than it had been in the 19th century. But the Empire

was not united. There was no coherent system of government, no

coordinated defence structure and no common economic policy. In

the words of historian Michael Howard, the Empire had 'become a

brontosaurus with huge, vulnerable limbs which the central

nervous system had little capacity to protect, direct or

control' (The Continental Commitment, 1972).

The Dominions

In the 19th century Britain had

begun the process of transforming the Empire into the Commonwealth. In 1867

Canada was granted dominion status, which allowed her complete

self-government in domestic matters although London retained control of her

defence and foreign policy. Dominion status was granted to Australia in

1901, New Zealand in 1907 and South Africa in 1910. The commitment of the

Dominions to the Empire remained strong, probably because most of their

white settlers were recent immigrants from Britain. Their contribution to

the Allied cause in the First World War was enormous. More than a million

men from the Dominions served in the various theatres of war, and 140,000 of

them were killed. This debt had to be acknowledged. The Statute of

Westminster of 1931 granted the Dominions complete independence.

The Dominions remained

well-disposed towards Britain, but they could not be relied on for

unwavering support. Disagreements over trade policy surfaced at the Ottawa

Conference in 1932. The Dominions were happy to see their exports entering

Britain without paying tariffs, but were not prepared to extend the same

privilege to industrial goods imported from Britain because they wished to

develop their own industrial capacity. The most they would agree to was an

increased tariff for non-British goods.

Australia and New Zealand were

the most loyal of the Dominions. Britain was their principal trading partner

and source of capital. For defence, they relied on Britain's oft-repeated

promise to send the British fleet to the Far East when necessary. This

spared them the expense of building their own armed forces. In 1939

Australia had an army of just a few thousand soldiers supplemented by a

voluntary militia whose members trained for only 12 days a year. There was

no air force to speak of and the navy comprised six cruisers, five First

World War destroyers and two sloops.

At the Imperial Conference in

May 1937, the Canadian Prime Minister suggested that public opinion in his

country recommended Britain to 'leave the Germans and French to kill each

other if they wanted to' but he also added that 'there would be great

numbers of Canadians anxious to swim the Atlantic' to help Britain in war.

All the Dominions disliked Britain's European commitments and did not want

to see her drawn into another European war, but they exercised little

influence over British policy. When war came in 1939, Australia, New Zealand

and Canada joined Britain immediately. In South Africa, the pro-British

premier had to overcome the hostility of Afrikaaners who remembered the Boer

War before he could secure parliamentary approval for a declaration of war

The Middle East

After the First World War

Britain took control of Iraq, Transjordan and Palestine from the defeated

Turkish Empire. Britain granted Iraq independence in 1932 but Palestine was

to prove difficult and costly to govern. In 1937, Britain's proposal to

divide Palestine between the indigenous Arabs and the immigrant Jews

provoked an Arab revolt. At the height of the Czech crisis in the autumn of

1938, Britain had more than 20,000 troops tied down in Palestine.

Ireland

Both Catholic and Protestant

Irishmen fought as volunteers in the British army during the First World

War. This was remarkable because Ireland was on the verge of civil war in

1914 over Britain's plans to grant the country home rule -in effect,

dominion status. In 1919 militant Catholic nationalists declared Ireland

independent and set up their own government in Dublin. Three years of

vicious fighting with the British authorities followed. In 1922 southern

Ireland was granted dominion status as the Irish Free State. The six

counties of protestant Ulster remained under British rule and Britain

retained the right to use three ports in the south. Relations between the

Free State and Britain were frosty principally because of the Ulster issue,

and from 1932 the two countries were engaged in a tariff war. By 1938, with

war in Europe looming, both sides were keen to settle their differences. The

tariff war was ended and Britain gave up her right to use the three ports.

This was a high price to pay for Irish neutrality because the ports would

have been invaluable in the Battle of the Atlantic in the Second World War.

But had Ireland been sympathetic to Nazi Germany, the consequences might

have been worse.

India

Britain had been preparing India

for dominion status since 1909, when

Indians were allowed

limited participation in the legislative process. Further

concessions were granted

after the First World War in which 1,200,000 Indians

I had served and 62,000

had died. Limited self-government was introduced in

I 1919 and extended in

1935. Indian nationalists were not content with these

cautious measures

and demanded immediate independence. Britain's

attempts to contain

Indian nationalism were unsuccessful - the Amritsar

Massacre of 1919, in

which British troops opened fire on an unarmed crowd

and killed 379 people,

and the frequent arrests of leaders such as Gandhi

served only to enflame

the situation.

The issue also threatened to

divide the Conservative Party in Britain. Churchill sat on the back benches

for most of the 1930s because he loathed the government's Indian policy. For

him the Indians were 'humble primitives' for whom 'democracy is totally

unsuited'. At times he mobilised significant support within the Conservative

Party. The future of India was unresolved when war broke out in 1939, and

the loyalty of India's population to Britain's cause could not be

guaranteed.

The legacy of the Treaty of Versailles

Britain and the Treaty

The peace settlement at the end

of the First World War appeared to give Britain everything she wanted. The

German fleet - the creation of which had been largely responsible for

Britain joining the war in the first place - lay scuttled at Scapa Flow. The

German overseas empire was confiscated and her colonies were divided among

the victorious allies. Britain's Prime Minister, David Lloyd George,

successfully insisted that Britain should receive some of the reparations

payments that Germany was required to make. All of this meant that when

other issues arose concerning the treatment of Germany, Lloyd George tended

to be magnanimous. British appeasement of Germany began at Versailles.

France and the Treaty

The French could not afford such

generosity. Despite victory in 1918, they were all too conscious of their

weakness. The north-eastern corner of the country had been devastated and

France had lost perhaps as many as 1,500,000 dead and 700,000 wounded in the

war. These losses were smaller than Germany's, but the consequences for

France were more serious. Her population was only two-thirds the size of

Germany's and her birth rate was stagnant. In the words of Professor Jacques

Nere, 'for the French and Germans in 1919, the ratio of men of an age to

bear arms was 1:2. Moreover, in the case of heavy industrial potential, even

after reconstruction of the devastated French areas, the ratio was 1 A' (The

Foreign Policy of France from 1914 to 1945, 1975). Furthermore, revolution

in Russia had deprived France of the alliance that could pressure Germany

from the east.

To the French it was essential

that the Treaty of Versailles should permamently disable Germany's potential

for aggression. French leaders hoped to detach the western bank of the Rhine

from Germany and either annex it to France or create an independent buffer

state. Pressure from the United States and Britain forced them to abandon

these hopes. Instead, the Allies decided to keep troops on the left bank for

15 years. A zone on both sides of the river was created. This was to be

permanently demilitarised - in other words, the Germans could neither

fortify it nor station troops there. The French also received an

Anglo-American guarantee against any unprovoked aggression by Germany. But

this became worthless almost immediately because in November 1919 the

American Senate, determined to have nothing more to do with Europe, refused

to ratify the Treaty of Versailles.

Disarmament

German disarmament

The Treaty of Versailles

demanded the immediate disarmament of the defeated powers; the needs of

French security required nothing less. The German army was reduced to the

size necessary to guarantee internal order, a mere 100,000 men, but was not

permitted tanks, heavy artillery or an air force. Her navy was reduced to

being a coastal defence force. Pious statements about Allied disarmament

were made at the peace conference, but nothing concrete was achieved.

The Washington and London Naval

Conferences

In 1921 the Americans invited

the major powers to a conference on naval limitation. The five-power treaty

signed by the USA, Britain, Japan, France and Italy in December 1921

established a fixed ratio for the size of their respective fleets of capital

ships (battleships and battle cruisers) of 5 : 5 : 3 : 1.75 : 1.75 Britain,

realising that she could not afford an arms race with the United States, had

signed away her naval supremacy. She also bowed to American pressure to

abandon the alliance with Japan, first signed in 1902. Nationalists in Japan

were outraged that their delegates had agreed to permanent inferiority, the

more so when the Washington ratios were applied to cruisers as well at the

London Naval Conference in 1930. For some historians, the origins of the

Second World War in the Far East can be traced to Washington. 'The British,

by ending the Japanese alliance, helped to strengthen those in Japan who

wished to follow more chauvinistic and aggressive policies. Ties with Japan

were weakened with no compensating tightening of relations with the United

States' writes C.J. Bartlett (British Foreign Policy in the Twentieth

Century, 1989). Yet it is difficult to see what realistic alternative was

open to Britain.

The Disarmament Conference

1932-34

Attempts to limit the size of

national armies proved even more difficult, and revived Anglo-French discord

about how to treat the Germans. The French were, as ever, worried about

their security, but the British believed that the inferiority imposed on

Germany at Versailles could not be maintained for ever. After a good deal of

stalling, the Disarmament Conference opened in Geneva on 2 February 1932.

The Germans walked out in September because they had not been granted

equality. Although French concessions persuaded them to return three months

later, Hitler withdrew Germany permanently from both the Disarmament

Conference and the League of Nations in October 1933. It became an objective

of British foreign policy over the next few years to try to tempt Hitler

back into the League. In 1934 the Disarmament Conference broke up without

agreement.

The impact of the Depression

The Wall Street Crash and the

Depression

When the American stock market

crashed in October 1929, it triggered a worldwide economic depression that

lasted until the mid-1930s. Thousands of American investors were ruined and

so demand for goods suddenly dropped. At the end of the 1920s much economic

activity in the United States had been financed by credit. This explains why

the Wall Street Crash so rapidly ruined businesses and produced high

unemployment. The American response was to protect her ailing industries by

imposing high tariffs on imported goods. These damaged the economies of

those countries that relied on exporting their goods to the United States.

Exporters of primary products such as food and raw materials were

particularly badly hit because the glut of the late 1920s had already forced

down the price of their exports. American investors also called in their

loans to Europe, which worsened the problems. This particularly affected

Germany, where the fragile recovery of the 1920s had been financed by

American investment.

The political impact of the

Depression

The severity of the economic

crisis made the system of reparations payments unworkable, and they were

duly cancelled at the Lausanne conference in 1932. This concession was not

enough to save the Weimar Republic in Germany. Hitler became Chancellor in

January 1933 because the Depression paralysed both the German economy and

its political system. Once he had established his dictatorship, he set about

destroying the Versailles Settlement and reestablishing German power in

Europe.

In Britain, economic problems

destroyed the Labour government in 1931. A National Government was formed

with sufficient electoral support to ride out the storm. But the crisis made

the governments of the 1930s reluctant to spend money on rearmament in case

the problems of 1931 returned.

France was unscathed at first,

but by 1932 France too was in difficulties with rising unemployment and

political instability. During the 1930s French politics became increasingly

polarised between right and left, making a coherent national response to the

threat of Germany almost impossible.

The impact of the First World War

The war to end all wars

Britain suffered 722,000 dead

and 1,676,000 wounded in the First World War. These losses were

unprecedented and created a widespread feeling that carnage on such a scale

should never be allowed to happen again. The war inspired a flood of

literature that graphically described its horrors and reinforced public

perceptions that the sacrifices of trench warfare had been futile. Modern

warfare, it seemed, was so shattering and terrible that no nation could

benefit from it. When the novelist H.G. Wells called it 'the war to end all

wars', he believed that no-one could possibly contemplate such destruction

again.

The outbreak of the war was

blamed on the alliance system and the arms race. It was widely believed to

have been an accidental and avoidable conflict, not the product of

aggression and malevolence. This implied that future wars could be averted

by disarmament and open diplomacy conducted in the League of Nations.

The wrong sort of war

Until 1914, Britain's method of

fighting had remained essentially the same for two hundred years. It was the

job of the Royal Navy to gain mastery of the oceans. The British Army was

little more than an Imperial police force, and if fighting on the European

continent was necessary, it would be done by Britain's allies whose armies

might be supplemented by small contingents of British soldiers. With the

brief exception of the Crimean War, no British troops had seen action in

Europe since the defeat of Napoleon in 1815. This strategy allowed Britain

to remain unique among the major powers in recruiting its armed forces

entirely from volunteers. The total strength of the Army in 1914 (including

the Regular Army, Reserves and Territorial Forces) was 733,514. This was

very small by European standards.

The First World War transformed

Britain's strategy. At the time of the

armistice, there were l,794,000

British soldiers serving on the Western Front

alone. More than five

million men served in the Army during the war, and 47%

of them became

casualties. The Royal Navy was reduced to a secondary supportive role, and

conscription was introduced in 1916 to feed the insatiable

demand for manpower After

1918, when the wisdom of fighting in France was

questioned, Britain

endeavoured to return to its traditional strategy

The Ten Year Rule

This thinking was strongly

reinforced by economic realities. In August 1919 the Cabinet agreed that:

'It should be assumed... that the British Empire will not be engaged in any

great war during the next ten years, and that no Expeditionary Force is

required for this purpose.' This became known as the Ten Year Rule, and it

justified immediate cuts in Britain's armed forces. Expenditure dropped from

£692 million in 1919-20 to £115 million in 1921-22 and it did not rise again

until 1934-35. Conscription was abolished in 1920, and manpower in the armed

forces sank to below pre-war levels.

In 1928, the Chancellor of the

Exchequer, Winston Churchill, in order to keep the spending estimates of the

service ministries in check, decided that the Ten Year Rule should be

annually renewed. It was only abandoned in March 1932 as a result of the

Manchurian crisis but, because the Disarmament Conference was still in

progress, British rearmament could not begin until 1934.

Britain's fighting services

Strategic difficulties

Between the wars there were

constant arguments between Service chiefs and politicians about how best to

use Britain's limited resources to defend the United Kingdom and the.

Empire. There were three inter-related issues:

♦ Which territories were most

under threat and from whom?

♦ Was the Army, Navy or Air

Force best suited to respond?

♦ How did the developing

technology of warfare affect the way the armed forces should be used?

These were both strategic and

diplomatic questions which became particularly hard to solve in the 1930s

when Britain faced simultaneous challenges from Germany, Japan and Italy.

The RAF

The First World War created

exaggerated fears of the destructive potential of air power in any future

conflict. In 1922, the Committee of Imperial Defence advised that, in the

next war, 'railway traffic would be disorganised, food supplies would be

interrupted and it is probable that after being subjected for several weeks

to the strain of such an attack the population would be so demoralised that

they would insist upon an armistice.' It followed that the only way to

prevent destruction was to build a bomber fleet large enough to deter an

enemy attack.

The importance of bombing

dominated strategic thinking about the role of air power until the late

1930s. But it did not mean that the RAF received any more money from the

Treasury. The Ten Year Rule implied that there was no urgency to build a

major bombing fleet, so the RAF suffered cuts along with the other two

services. It was used as a cheap and effective method of policing far-flung

Imperial territories.

When the government concluded in

1934 that Germany was Britain's 'ultimate potential enemy', priority was

given to rebuilding the RAF as a effective deterrent. The Defence White

Paper of March 1935 declared that the 'principal role' of the RAF was 'to

provide for the protection of the United Kingdom and particularly London

against air attack.' In the various expansion schemes produced between 1934

and 1938, priority was given to the production of bombers whose role in war

would be to attack German cities in retaliation for any air assault on

Britain. This strategy underpinned the government's reluctance to send the

Army into Europe again - if we could bomb the Germans into submission, we

"would not need to send soldiers to fight them.

Strategy changed in the late

1930s. The development of the Hurricane and the Spitfire meant that Britain

possessed two new monoplane fighters with the speed and manoeuvrability to

shoot down bombers. At the same time, a chain of radar stations, which could

detect the approach of enemy aircraft, was being built across the south and

east of Britain. The Minister for the Co-ordination of Defence, Sir Thomas

Inskip, challenged the bomber offensive strategy in a report presented to

the Cabinet in December 1937 and suggested that priority should be given to

the production of fighters. Strategy remained essentially defensive and

dovetailed with Chamberlain's diplomatic objective of appeasing Germany.

Despite developing greater

confidence that an enemy air assault could be warded off, British planners

continued to believe that German bombers could inflict terrible losses (see

Table 2 on page 47). In September 1938 the Luftwaffe (German air force) was

thought to be capable of dropping 945 tons of bombs on England in a single

day. The Air Raids Precautions department estimated that there would be 50

casualties per ton. This explains why the Ministry of Health was expecting

600,000 deaths- and 1,200,000 wounded from air raids alone in the first six

months of war. In fact, German bombers did not have the range to reach

England until their armies captured the Low Countries and northern France in

1940, and the total number of civilian deaths in Britain during the whole of

the Second World War was 60,000.

The Royal Navy

After the First World War the

Navy resumed its place as Britain's principal service. Its peacetime

functions were to protect Britain's sea-borne trade route and defend the

territories of the Empire. But its effectiveness was progressively eroded by

government financial limitations and by international treaties. At the

Washington Naval Conference of 1921-22 (see also Chapter 2, page 12) the

Navy had to accept equality with the Americans. Given that the likelihood of

war against the USA was negligible, the Treaty at least ensured that

Britain's navy was considerably larger than that of any potential rival. The

Washington signato-| ries also agreed not to build any new battleships or

battle-cruisers for ten years. At the London Naval Conference in 1930 this

ban was extended for a further five years, and Britain also agreed to

limitations on the rebuilding of her cruiser and destroyer fleets.

For most of the inter-war period

the Royal Navy regarded Japan as its most

likely potential enemy. This was

welcomed by the governments of Australia

and New Zealand, who relied on

the British fleet to defend them. It appeared

to be endorsed by the

British government as well because, in response to the Manchurian crisis,

the rebuilding of the base at Singapore was finally resumed in June 1932

after the postponements and delays of the 1920s. However in

1934, the threat posed by Hitler pushed Japan into second place in

Britain's

list of enemies.

The Navy's strategic plans met

a formidable obstacle in the shape of Neville Chamberlain (left), who was

Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1931 until 1937 and then Prime Minister. He

was convinced that Britain could not afford to do anything other than ignore

Japanese expansion. By 1939 Japan had slipped to third place behind Italy in

the list of enemies, and the Chiefs of Staff accepted that whether or not

the fleet could be sent to Singapore would 'depend on our resources and the

state of the war in the European theatre'. The commitment to defend the Far

East had been tacitly abandoned.

It was not just Treasury

penny-pinching and government strategic priorities that weakened the Royal

Navy. Its tactical thinking was somewhat conservative. Naval planners

continued to underestimate the vulnerability of warships to air attack, and

insufficient emphasis was given to the construction and deployment of

aircraft carriers. When the war began in 1939 Britain possessed only six

aircraft carriers, four of which were converted warships.

The Army

The number of territories the

Army was expected to defend had increased but, after 1918, its size was

rapidly cut and by 1920 there were fewer men serving than there had been ten

years earlier. The government's enthusiasm for cost-cutting coincided with a

widespread feeling that the commitment of a huge army to fight in France had

been a terrible aberration. British people remembered the costly losses of

the battles such as the Somme and Passchendaele rather than the spectacular

victories of 1918. It was assumed that only generals who were insensitive,

ignorant and out of touch could have sent so many men to their deaths on the

Western Front. When the cartoonist David Low wanted to invent a character to

be the archetypal voice of pompous, reactionary stupidity, he made him an

army officer- Colonel Blimp.

To some extent the Army

reinforced these negative images. Its officers continued to be drawn from a

narrow upper-class social group who prized sporting rather than intellectual

achievement. During the 1930s the British Army managed to squander the early

lead in the use of machines and vehicles that it had established over its

continental rivals. In the words of historian Edward Ranson, 'Britain

entered World War Two without an effective armoured force, lacking clear

ideas about tank warfare, and with vehicles with severe design and

operational limits' {British Defence Policy and Appeasement between the Wars

1919-1939, 1993). These failings were the result partly of government

financial stringency and partly of squabbles between senior officers about

the role of mechanised units in modern warfare. But they were also the

product of confusion about the strategic role the British

Army was expected to

play.

Strategy and diplomacy

The Defence Requirements

Committee

In 1922 the Cabinet told the

Army that its responsibilities for the foreseeable future were home security

and Imperial defence. Throughout the inter-war period there were more

British troops in India than anywhere else in the Empire outside the United

Kingdom. In 1933 the government established a Defence Requirements Committee

(DRC) to advise on strategy and rearmament. Its first report, produced in

February 1934, identified Germany as the 'ultimate potential enemy against

whom our "long range" defence policy must be directed'. The DRC recommended

rebuilding all three services, including the preparation of a small

Expeditionary Force of the British Army to fight on the Continent. It

pointed out that the Low Countries were now more vital than ever to British

security, because possession of their airfields would allow German bombers

to reach industrial heartlands in the Midlands and the North.

The Cabinet, dominated by

the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Neville Chamberlain, disagreed. Chamberlain

wanted to deter the Germans, not fight them. He insisted that priority

should be given to rebuilding the bombing , capability of the RAF. The

notion of equipping an army to fight in Europe was dropped. The Cabinet

believed that public opinion would not accept it.

Avoiding a continental

commitment

The DRC reported again in

November 1935. The scale and pace of German rearmament was alarming, and the

Abyssinian crisis (see Chapter 4, page 28) had transformed Italy from a

potential ally into a Mediterranean menace. The DRC report emphasised the

fundamental problem facing British strategy and diplomacy: 'It is a cardinal

requirement of our National and Imperial security that our foreign policy

should be so conducted as to avoid the possible development of a situation-

in which we might be confronted simultaneously with the hostility of Japan

in the Far East, Germany in the West, and any power on the main line of

communication between the two.' The Cabinet scarcely needed reminding of

this, but it reinforced Chamberlain in his hostility to the idea of

preparing an Army for fighting in Europe, even though the DRC still

recommended doing so. When the Arab Revolt broke out in 1937 the need to

send more troops to Palestine pushed the 'continental commitment' even

further into the background.

Economic problems

The impact of the First World

War on Britain's economy

The First World War did immense

damage to Britain's economy and accelerated the decline that had begun in

the late 19th century. During the war Britain was less able to supply her

pre-war export markets. As a result, countries either produced their own

goods or bought them elsewhere. Lancashire, which before the war had

dominated the world market in cotton textiles, found itself undercut by

Japan and India, whose labour costs were lower. Britain's cotton exports to

India declined by 53% between 1913 and 1923. Clydeside, which built a third

of all the world's ships in 1913, faced post-war competition from the USA

and Japan. Britain's export markets for coal were similarly devastated. The

number of unemployed in Britain between the wars never fell below a million.

The First World War also saddled

Britain with huge international debts. During the conflict Britain lent

£1,419 million to its allies, mainly France and Russia, and borrowed £1,285

million, chiefly from the United States. After the Russian Revolution of

1917 the new communist government refused to honour the debts it had

inherited from the Tsarist regime, but the Americans continued to demand

repayment of the money owed to them by Britain and France: A large slice of

government revenue in the post-war years was devoted to paying off Britain's

war debt to the United States.

'The fourth arm of defence'

The Wall Street Crash in the

United States in 1929 caused serious economic problems in Britain. Exports

fell, unemployment rose to triree million and, in 1931, Britain was forced

to abandon the Gold Standard - a cherished symbol of the strength and

stability of the pound. The politicians who dominated the National

Government, which had been formed in 1931 to deal with the crisis at its

worst, were haunted by the fear that rash economic policies would cause the

problems to recur.

During the 1930s the Treasury

maintained that Britain's economy was 'the fourth arm of defence'. They

argued that, as a country dependent on imports for food and many industrial

raw materials, Britain needed to maintain a healthy balance of payments.

They argued that rapid rearmament would cause a balance of payments deficit

because the normal pattern of trade would be upset. If factories switched to

war production they would not be producing export goods but would still

consume imported raw materials. Britain's balance of payments problems would

cause foreign investors to sell the pound and a crisis on the scale of 1931

would recur. The Treasury nightmare was that Britain would enter a war with

a weak pound and few reserves, and so would be unable to survive a major war

without becoming bankrupt after a few months. Britain, it seemed, faced a

dilemma. Rapid rearmament to keep pace with the dictators would bankrupt the

British economy. Slow rearmament, based only on what the nation could

afford, might mean that the country's armed forces were not strong enough to

cope with an enemy attack.

The Ten Year Rule also left an

unfortunate legacy. When the government did decide to rearm, it found that

the munitions industry, starved of orders since 1918, had shrunk in size and

capacity. The biggest problem was the lack of skilled labour. Although there

was a vast pool of unemployed workers, few of them had the skills to operate

machine tools or train others in their use. The government ruled out

compelling skilled workers to transfer from consumer industries to armaments

factories because, as the Cabinet concluded in 1936, 'any such interference

would adversely affect the general prosperity of the country and so reduce

our capacity to find the necessary funds for the Service programmes. It

would undoubtedly attract Parliamentary criticism.'

Economic appeasement

Treasury officials, like their

Foreign Office counterparts, were keen on appeasement and believed that the

government should do everything in its power to reduce the number of

Britain's potential enemies. Some officials argued that economic

difficulties in Germany explained why the Nazis were so aggressive. As a

Foreign Office memorandum put it in January 1936, 'If ... we believe that

nazism is in reality a symptom and not a cause, then it is logical to deal -

or at any rate attempt to deal - with it by attacking the cause itself. And

what is the cause? Obviously, economic distress.'

Neville Chamberlain, who played

an important part in shaping Britain's foreign policy even when he was

Chancellor of the Exchequer, believed that economic policy was vitally

important to the solution of Europe's diplomatic problems. He shared the

Treasury view that German aggression stemmed from economic difficulties. He

maintained that the Versailles Settlement, by robbing Germany of important

industrial territories in Europe and her overseas colonies, had made the

Germans determined to recover them, by war if necessary. If, thought

Chamberlain, British diplomacy could help to secure their return, the

Germans would have no need to go to war, or even build up armaments in

preparation for war.

Chamberlain and the Treasury

officials were fortified in this view by a mistaken, but understandable,

interpretation of German internal politics. They believed that Hitler was

receiving advice from two rival sets of advisers. One group, whom the

British thought to,be 'moderates', included men such as Schacht, the German

Economics Minister, and was believed to share the British view of how to

solve Germany's problems. The other group, designated 'extremists' by the

British, was thought determined to make Germany stronger

by conquest and war.

Chamberlain hoped that judicious concessions to Germany would increase the

power and influence of the 'moderates'. This would not only make it

unnecessary for Germany to continue her preparations for war but would also

reduce international tension. Even as late as February 1939, Chamberlain

argued, in a speech in Birmingham, that a mutually beneficial Anglo-German

economic agreement could help avoid recession and rising unemployment in

Britain.

Unfortunately for Chamberlain,

although there were 'moderates' in Germany, their influence was negligible

after 1936 when Hitler demanded that the German economy should be ready for

war by 1940. Schacht, who dominated German economic policy in the first

years of the Third Reich, resigned from the Economics Ministry in 1937

because he could not restrain Hitler from ignoring economic realities in

Germany's rapid rearmament programme. Chamberlain's mistake was to assume

that Hitler was a rational

leader Economic

appeasement failed because Hitler did not want to be

appeased.

Popular opinion

The Franchise Act of 1918

increased the electorate from just under eight million to over 21 million,

and gave women over 30 the vote for the first time. After 1928 Britain could

be described as truly democratic because all men and women over the age of

21 could vote. This meant that politicians were much more conscious of

public opinion in shaping their policies.

Hostility to rearmament

Finding out exactly what the

public felt about foreign policy issues was difficult because the first

opinion polls in Britain were not established until 1937. However, there did

appear to be some widespread assumptions that politicians were reluctant to

challenge. The first and most important of these was the belief that another

conflict like the First World War could be avoided if the nations of Europe

cut down their armaments. Spectacular evidence of this seemed to be provided

by the East Fulham by-election of October 1933. The Conservative candidate,

defending a majority of more than 14,000 votes, advocated rearmament. He was

defeated by nearly 5,000 votes by his Labour opponent, who supported

disarmament. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fulham_East_by-election,_1933)

The result had a considerable influence on the Conservative leader, Stanley

Baldwin, who became convinced that rapid rearmament would mean defeat at the

polls in the next general election. Faith that the League of Nations could

settle international disputes without recourse to war was another

widely-held belief. At its peak in 1931 its British supporters' club - the

League of Nations Union - could boast more than 400,000 members. In 1935 the

Union published the result of its 'Peace Ballot' of more than 11 million

people, which appeared to give a ringing endorsement of the League and its

principles, including international disarmament. The rapturous reception

given to Chamberlain when he returned from Munich (see Chapter 5) suggests

that, even as late as September 1938, many people in Britain were anxious to

avoid war and actively supported the policy of appeasement.

British domestic politics

The political landscape in

Britain had been altered by the First World War. By 1922 the Labour Party

had emerged to challenge the Liberals as the principal opposition to the

Conservatives. The rise of the Labour Party - which had adopted an

explicitly socialist constitution in 1918 -worried the Conservatives. Tory

leaders believed that only moderate, unadventurous policies would be

sufficiently popular to win over former Liberal voters and keep themselves

in power. Defeat might deliver the nation into the hands of the wild men of

the left thought to be lurking behind the leadership of the Labour Party. As

it happened, similar calculations were being made by the Labour leaders, who

were convinced that they could only achieve power and pick up their share of

former

Liberal votes if their

party adopted responsible and cautious policies. The result was a political

consensus in which both main parties aimed to control the middle ground of

British politics and avoid policies, particularly concerning foreign and

defence issues, that courted electoral unpopularity. Winston Churchill, as

Chancellor of the Exchequer in the 1920s, summed up this thinking when he

opposed more money for the Navy because he could not 'conceive of any course

more certain to result in a Socialist victory.'

Spending priorities

The First World War and the

advent of democracy altered government spending priorities. As Table 4 on

page 47 shows, expenditure on welfare took a much higher proportion of the

government's budget in the 1930s than it had done in the days before the

First World War. After the sacrifice of the war, the demands for extensions

to the welfare responsibilities of government were irresistible. War

pensions, more generous dole payments and extensions of the scope of

National Insurance all added to the demands on the Exchequer in the post-war

years, and no government, much less one striving to hold the middle ground,

could contemplate irreversible cuts in these benefits in order to finance

rearmament.

The impact of Hitler

Hitler as Chancellor

There was little alarm in

Britain when Hitler became German Chancellor in January 1933. The Daily Mail

even rejoiced that Germany had 'a stable government at last' and welcomed

Hitler, with his 'good looks and charming personality', taking on 'the

mantle of Bismarck'.

In speeches and interviews

during 1933, Hitler stressed his peaceful ambitions and emphasised his

desire, first expressed in his autobiography Mem Kampf, for an understanding

with Britain. The British government responded cautiously. While anxious to

reach agreement with Hitler, they were exasperated by his behaviour. Soon

the evidence of German rearmament in defiance of the Treaty of Versailles

was plentiful, and in July 1934 the murder by Austrian Nazis of Chancellor

Dollfuss briefly excited fears of a German invasion of Austria.

The Stresa Front, April 1935

German rearmament in defiance of

the Treaty of Versailles became public knowledge when, on successive

Saturdays in March 1935, Hitler announced the existence of the Luftwaffe and

the reintroduction of conscription. This alarmed Italy, France and Britain

so much that their heads of government and foreign secretaries met, on

Mussolini's invitation, at Stresa in Italy. The Stresa Conference produced

an impressive declaration that the three powers would 'act in close and

cordial collaboration' to oppose 'any unilateral repudiation of treaties

which may endanger the peace of Europe'.

But the unity of Stresa was

bogus. None of the three was prepared to act without the support of the

others, and there were plenty of issues to divide them. Mussolini was

already moving troops through the Suez Canal in preparation for his

invasion of Abyssinia in the autumn. The lack of any British protest led him

to believe that he had tacit approval for his invasion. He had already

secured the secret support of the French, who were anxious to keep him as an

ally against Hitler. The British Cabinet had agreed, before the conference

began, 'to take no action [against Germany) except to threaten her'

The Anglo-Cerman Naval

Agreement, June 1935

The emptiness of the Stresa

declaration became apparent two months later when Britain signed her

bilateral Naval Agreement with Germany. Without prior consultation with

France or Italy, Britain agreed to allow the Germans to build a fleet of up

to 35% of the size of the Royal Navy.